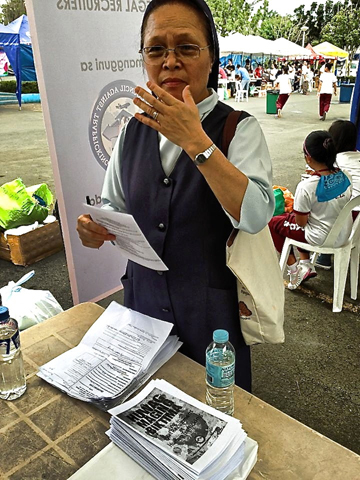

A nun reads through an anti-trafficking leaftlet handed out to Typhoon Haiyan survivors at the Philippine Air Force Base in Pasay City, Philippines, beginning Nov. 16. (Courtesy of Inter-agency Council Against Trafficking)

A formidable multi-billion-dollar human-trafficking industry has driven Catholic religious women to collaborate among themselves and with other sectors of society to stop what Pope Francis has called "the most extensive form of slavery of the 21st century."

Since International Union of Superiors General (UISG) established Talitha Kum ("Little girl, arise") in 2009*, the anti-trafficking network of women religious, has developed a program of activities banking on partnerships established by the UISG central office in Rome as well as a network of local anti-trafficking teams.

Talitha Kum has also linked up with government, professional, faith-based and other organizations, said Sr. Estrella Castalone, its coordinator, at a recent Asia-Oceania conference of women religious in Tagaytay City, south of Manila.

In her presentation ahead of Thursday's International Day against Trafficking, Castalone said, "My dearest sisters ... We know that this slavery has a feminine face. It behooves us, women religious, to join hands and put a stop to it. Talitha Kum takes this commitment and we enjoin you to support us, individually or as a congregation."

For Castalone of the Salesian Sisters of St. John Bosco, partnership is a "significant component" of Talitha Kum's approach. Without this, it is impossible to combat the intricate web of syndicated operations she illustrated in her slideshow.

As religious, "we can only move and be involved within the parameters of our consecrated life," Castalone pointed out to the more than 65 nuns and members of partner groups who joined the Asia-Oceania Meeting of Religious (AMOR XVI) in November.

Besides, victims of human trafficking often undergo a harrowing experience that requires a "long and difficult process of healing and recovery ... needing interdisciplinary case management approach," she said.

Partnering with government and private bodies also serves the need for job placement and alternative livelihood options for victims.

"We realize that as religious, we cannot be involved so much in the prosecution process," Castalone said.

She acknowledged the help with funding provided by Conrad N. Hilton Fund for Sisters and the continuous training and support from International Organization for Migration.

Protecting the vulnerable

"Trafficking in persons" and "human trafficking" involve "recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, or obtaining a person for compelled labor or commercial sex acts through the use of force, fraud, or coercion."

People may be considered trafficking victims regardless of whether they were born into a state of servitude, were transported to the exploitative situation, previously consented to work for a trafficker, or participated in a crime as a direct result of being trafficked.

At the heart of this phenomenon is the highly organized traffickers' goal of exploiting and enslaving men, women and children using deception and coercion, Castalone said. "It is only through an equally well-organized network that links the countries of origin to those of transit and destination that we can prevent the weakest and the most vulnerable from becoming a human commodity."

About 12.5 million to 27 million people reportedly live within the criminal circle of human trafficking, with women and girls accounting for 75 percent of victims. Fifty-eight percent of detected cases involve sexual exploitation, while 36 percent were for forced labor.

Castalone said she worries about the rising number of child victims. Victimized children made up 27 percent of the cases between 2007 and 2010, up from 20 percent in 2003 through 2006.

"What troubles us most is the fact that behind all these statistical figures are the harrowing experiences of trafficked victims, mostly women and girls, who often experience physical and emotional suffering, trauma, rape, threats, and in some cases, death," Castalone said.

She also expressed concern for protecting and restoring the dignity of trafficked people. "They become invisible. They become a commodity, treated like objects for the 'buy and sell' business. They are no longer treated as human beings created in the image and likeness of God," Castalone said.

She recalled how this concern compelled UISG's executive board to establish Talitha Kum on Sept. 21, 2009, so consecrated women could "share and maximize resources that religious life has on behalf of prevention, awareness raising and denouncement of trafficking in persons, and protection and assistance of victims and vulnerable persons."

Sisters' network

Talitha Kum conducts counter-trafficking missions through 22 member networks in 75 countries with more than 600 sisters involved.

In Africa, four groups of sisters work in a total of 26 countries, and one network operates in North America based in Canada. Three operate in Latin America to stop trafficking of persons in seven countries and 21 states.

Two member networks in Asia address trafficking-related concerns in 14 countries, while Talitha Kum explores ways to link with human trafficking "hotspots" in the region, including Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Pakistan.

Sisters and laypeople affiliated with Religious in Europe Networking against Trafficking and Exploitation embark on counter-trafficking initiatives and advocacy in 17 countries.

Talitha Kum's approach follows the Palermo Protocol of 2000 for the protection, prevention and prosecution dimensions. Castalone adds a fourth dimension, partnership, which she says is crucial to impactful engagement.

To offer protection for victims, networks of sisters put up and operate shelters, houses and centers where they can rest and have food, clothing and some simple medical care.

"This is urgent because trafficked victims often find themselves at a loss on how to pick up the shattered pieces of their life," Castalone said.

Nuns also give victims counseling and debriefing, legal assistance and skills training aimed at their healing and recovery for an eventual reintegration into society as healthy, active and productive citizens or going back to their country of origin.

Putting up victims in homes is sometimes risky, as experienced by sisters in Sri Lanka who rescued girl soldiers. At times, offering shelter is not possible. Medical Mission Sr. Dagmar Plum works in a detention center in Eisenhüttenstadt near the Polish-German border among women who are waiting for their deportation.

Most of the female detainees are victims of trafficking and forced prostitution.

Consolata Missionary Sr. Eugenia Bonetti, 2013 European Citizen's Prize awardee, and a group of sisters from various congregations minister to women awaiting repatriation at the Centre for Identification and Expulsion in Ponte Galeria in Rome every Saturday. They hail from Africa, the Arab countries, Eastern Europe, countries of the former Soviet Union, Asia, and Central and South America. Bonetti also works to obtain legal status for women without proper documents.

Sisters in the Talitha Kum network have been involved in rescue operations of trafficked victims and bringing them to safety in Singapore, Sri Lanka, India, Germany, the Philippines, Australia and Italy.

"As a whole, however, in this ministry of pastoral care, protection and assistance of victims, we realize that healing and recovery is a long, complex and difficult process," Castalone said.

She shared a feeling of helplessness in the prosecution of perpetrators. "You see, a stash of cocaine is incontestable evidence of a drug crime, but a terrified and intimidated woman -- or worse, still a girl -- without documents, in a foreign country, is unwilling to testify in court," she said.

Some network members ask whether their efforts were simply "cleaning up the mess" left by the traffickers. "We want to look deeper into this reality to ask ourselves, 'What could be our cutting edge?' " Castelone said. She said she hoped their efforts at prevention would be the benchmark of their counter-trafficking drive.

To prevent vulnerable people from falling prey to illegal recruiters and human traffickers, Talitha Kum's sisters train religious and lay pastoral workers. Talitha Kum's team of trainers has conducted courses for women religious in India, Peru, Kenya and Costa Rica. At the end, participants sign up for a network in their country.

Sisters also conduct seminar-workshops, public meetings, conferences and forums as well as publish books and booklets, primers, posters, fliers and postcards. They also produce videos, mini-films, theatre and street plays to increase public awareness and put vulnerable people on guard. They tap schools of their congregations for information campaigns integrated in the social studies curriculum.

Talitha Kum organizes anti-human-trafficking campaigns such as petitions and public declarations, particularly during world events involving massive human mobility, which is a fertile ground for human trafficking, such as the 2010 Football World Cup in South Africa and the 2012 Olympics in London.

In November, member networks from 17 countries in Latin America gathered with sisters from 20 states of Brazil for a preparatory workshop to lay out the details of a counter-trafficking campaign related to the 2014 World Cup of the International Federation of Association Football set to start June 12 in their country.

Talitha Kum members also offer skills training and financial assistance for micro-industries, especially for women and youth in depressed areas to counter the attraction of indiscriminate migration, Castelone said.

*An earlier version of this story had the incorrect date.

[N.J. Viehland is NCR's correspondent in Asia.]